De Rally

The five participating teams and their cars arrived in the Chinese port of Shanghai on 16 May 1907. The start of the race was greatly delayed by the Chinese authorities. The participants were not welcomed with open arms in Peking; the imperial family and the government thought that the participants were spies, and that they were part of a Western plot to investigate the military strength of China. A whole host of ministries and bureaucrats assumed that the race was an excuse for the Europeans to infiltrate Peking in their cars and to thus take control over the city. Despite intensive diplomatic contact between the various parties, the Chinese court refused to grant permission for the cars to drive through Peking due to the fact that the cars did not yet have a legal status at that time. Donkeys had to be used to transport the cars through Peking. A problem arose during the discussions regarding approval for the race: there was as yet no Chinese word for “motor car”. By analogy with the train, which the Chinese called “fire carriage” (huo che), they named the motor car “oil carriage” (qi che). Permission to depart was finally granted on 10 June.

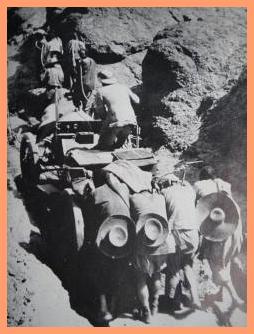

To begin with, the cars drove in convoy, making use of large numbers of carriers to carry the cars over the mountains to the north of Peking, and to lift them over the Great Wall of China. It goes without saying that progress was very slow in this first phase of the race. It is claimed that all the teams had agreed to stick together throughout the event. However, the “Itala team” left the rest of the group after the second night and continued the journey through the Gobi desert individually. The rest of the participants didn’t see them again during the rally. Prince Borghese, the leader of the Itala team, had his own fuel as well as political and administrative resources allowing him to continue the journey without the others.

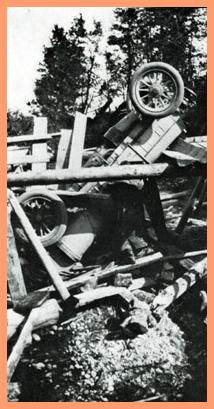

Close to Lake Baikal, a bridge gave way under the Itala.

On the third day, the Contal team found itself in extreme difficulties, and lost its way. They ran out of fuel in the Gobi desert and had to abandon their vehicle there. The Contal team suffered exhaustion and extreme thirst, resulting in fever and dysentery. The driver was in such a bad state that he was left with a Mongolian tribe to be cared for.

The two De Dions were guided carefully across the bridge over the Cha Ho river.

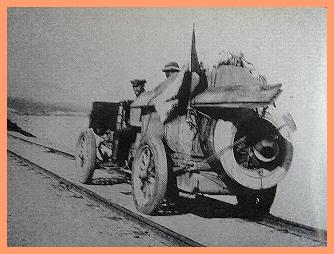

At 15 kilometers per hour, the Itala jolted its way over the railway line alongside Lake Baikal.

The two De Dion teams and the Spyker stayed together as far as Lake Baikal, where the Spyker suffered technical problems and the De Dion teams went ahead without the Spyker team. Godard, the driver of the Spyker, caught them up again later, but it is uncertain whether or not he cheated by travelling part of the route by train.

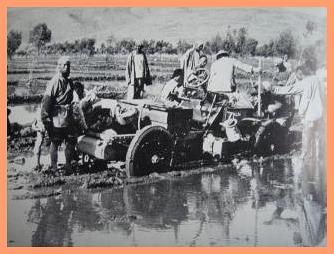

The journey was extremely difficult for all the participants. Rivers had to be crossed. This was done by dragging the cars through the river using oxen, or floating them across on self-made rafts. The cars frequently got stuck in paddy fields and desert sand. They also gave the “Great Urga Lama” a lift, and they had to leave crates of champagne behind in the Gobi desert to make the cars lighter. All the participants suffered from dysentery and other illnesses. They all encountered problems in trying to get past Lake Baikal, and all made use of the Trans-Siberia express railway line, as some stretches of road were impassable.

The Great Urga Lama being shown the Spyker. Beside him (wearing a helmet) is Godard.

The Itala team arrived first in Paris, on 10 August, despite a detour from Moscow to St. Petersburg to attend a party. The Itala team took 61 days to complete the course, covering an average of 250 kilometers per day. The De Dion and Spyker teams arrived in Paris together two weeks later.

.thumbnail.gif)